An Encyclopedia of Silence and Sound

Pareidolia—the tendency to perceive a specific, often meaningful image in a random or ambiguous visual pattern (think of seeing animals in clouds or faces in tree knots)—is quite a wonderful concept, one that certainly deserves its own fancy name. I think my favorite examples are in the stars, like when I was in Greece this year and the night sky was so perfectly clear and painted with constellation after constellation and I could look up and think quite loudly things like yes yes that really DOES look like a scorpion!

It’s also a word that has something of a silent E in it, which is easily—not even a question, really— the most famous of all silent English letters. It’s odd, isn’t it, to consider that across our entire lexicon, more than half of our alphabet is used silently in some word or another. The silent E, though, carries enough force to have a rule of its own: when present, the preceding vowel becomes long.

This—and other linguistic directives like it—are known as phonotactic rules, which I also consider to be a lovely word (with something of a silent H), especially when spoken aloud: those short O’s and the pleasing repetition of the vowel-separated T and C. Their purpose? To define how sounds are permitted be arranged in the words of a language. Rules, then, that govern the order and sound and silence of every word we speak.

A line can be drawn backwards in time that connects Bob Dylan to the Beat Generation to surrealism to French symbolism, then to the “volatile and peripatetic” poet, Arthur Rimbaud. Rimbaud stopped writing poetry at the age of twenty-one, having written it for only five years. The phrase le silence de Rimbaud is used to describe his abrupt abandonment.

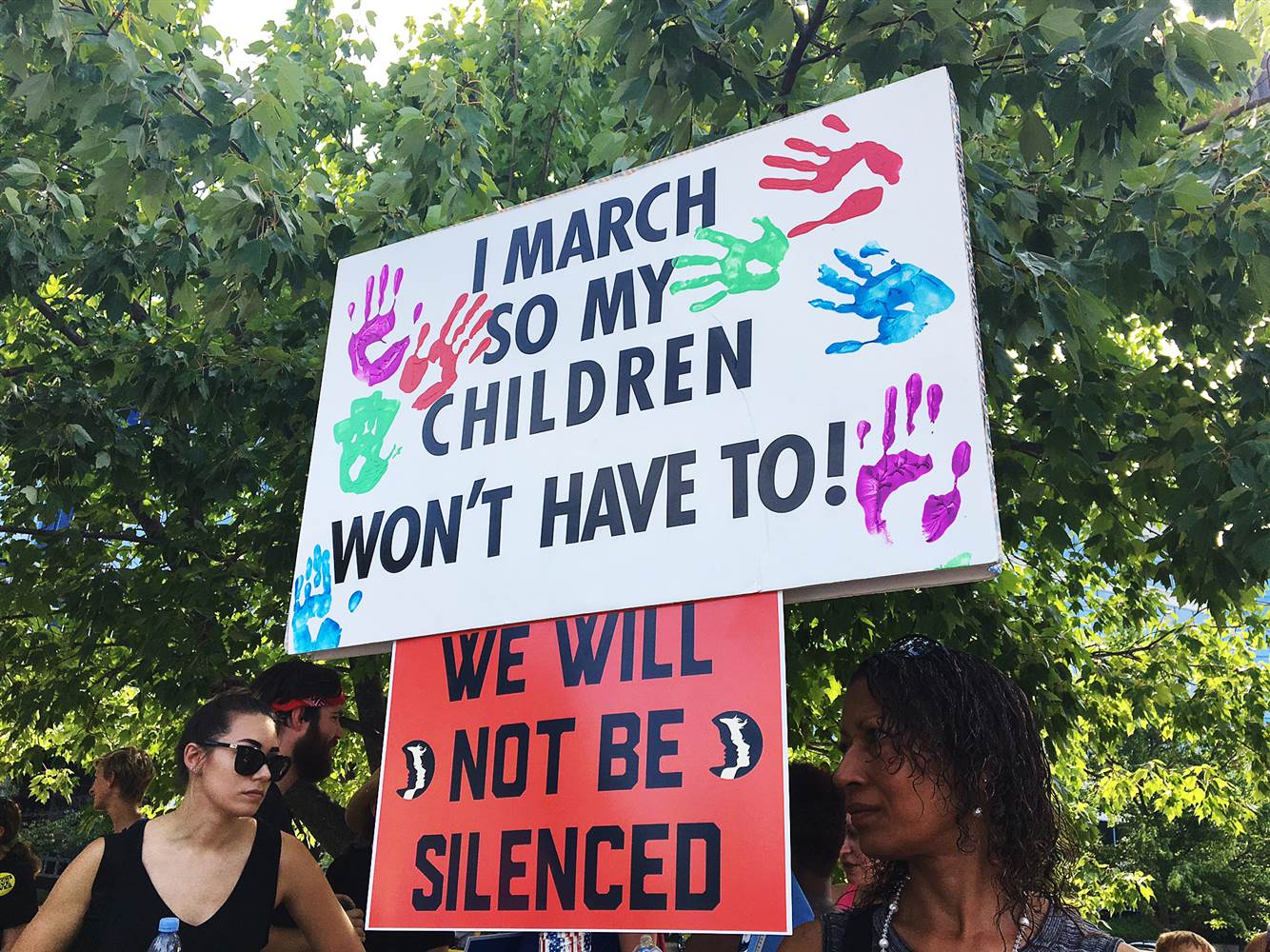

A few photos from the 2017 Women's March. Where (among other things) the act of silencing—and the refusal to be silenced—were counterposed forces.

On the first Wednesday of each month, the Museum of Modern Art opens its doors early (from 7:30am until 9). It encourages:

…visitors to take time to look slowly, clear your head, silence your phones, and get inspiration for the day and week ahead. Enjoy the serenity of being surrounded by Claude Monet’s monumental Water Lilies, find space for personal reflection in the minimalist canvases of Agnes Martin, or see the sublime in the colors of Mark Rothko.

These mornings are called Quiet Mornings, and they are lovely lovely. When you stroll around, you see a yawning New York in first gear, watching a rare sample of its slow, morning paces.

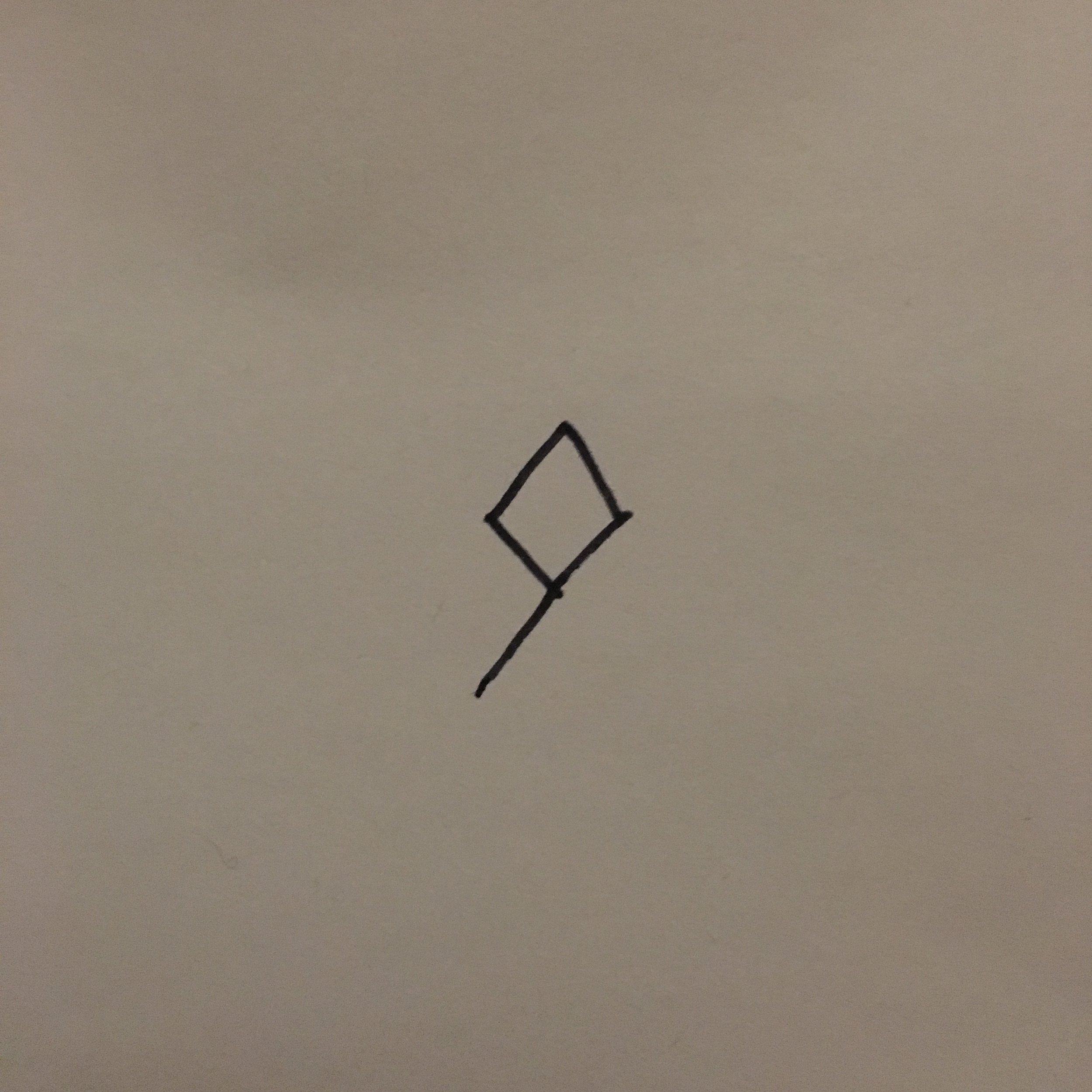

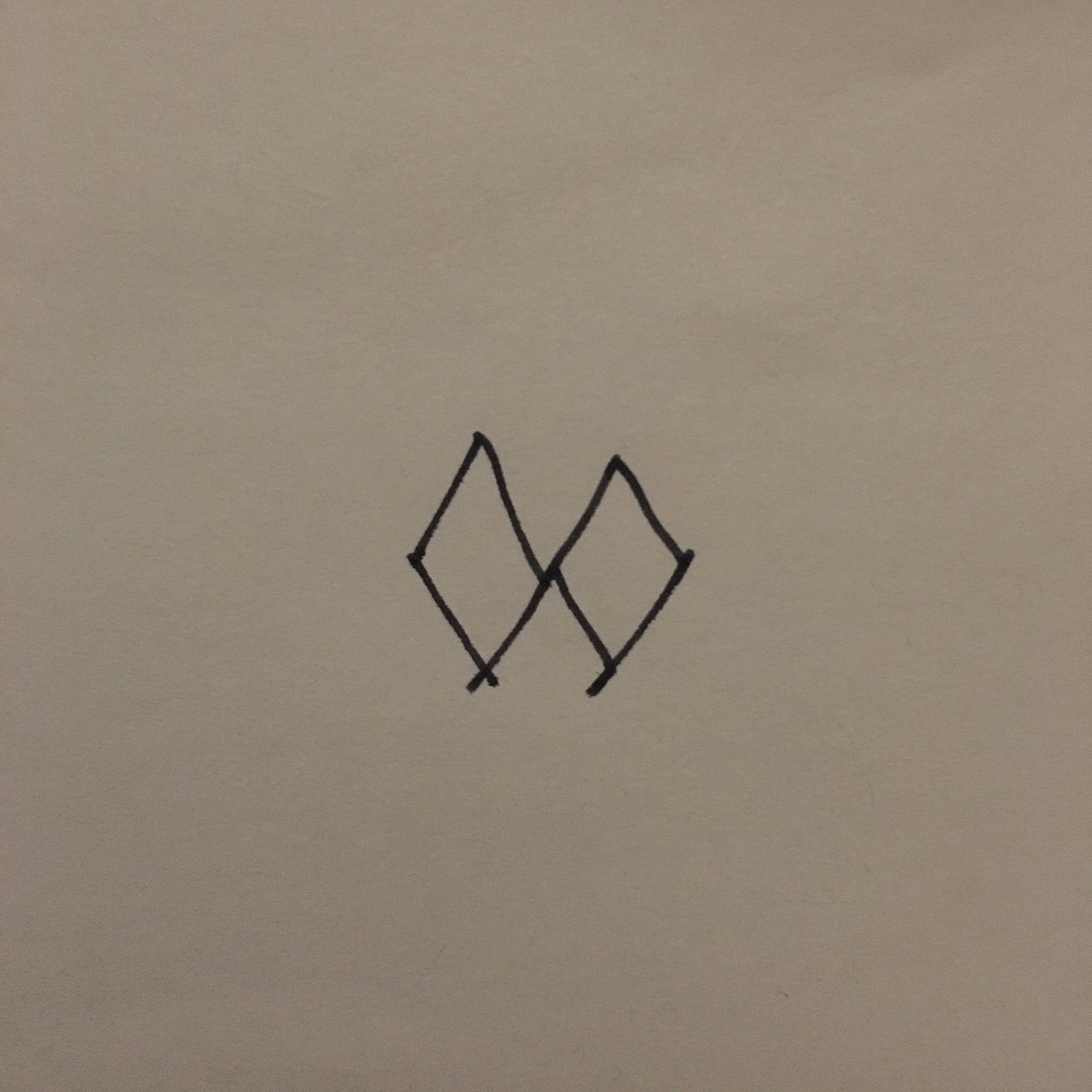

Here are two hobo signs (that is, the markings they would draw on bridges and fences and trestles to communicate with each other—to find work, get a meal, avoid danger, and more). Both are variations on diamond shapes: left means stay quiet, the right, hold your tongue. The first was more suggestive: move quietly, walk in the shadows, keep your head down; the second discouraged responding to provocative comments—anything derisive or critical—when you were on the road. Both were preventative: soft steps and wordlessness, that's how you stay alive.

I realize that, in speaking to you this afternoon, there are certain limitations placed upon the right of free speech. I must be exceedingly careful, prudent, as to what I say, and even more careful and prudent as to how I say it. I may not be able to say all I think; but I am not going to say anything that I do not think.

—Eugene V. Debs, from his speech to the Socialist party of Ohio state convention, Canton, Ohio (June 16, 1918).

But the character of every act depends upon the circumstances in which it is done...The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic...The question in every case is whether the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent. It is a question of proximity and degree.

—Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. (later to become a staunch defender of First Amendment rights), from his opinion in Schenck v. United States (1919). The same logic was used to convict Eugene V. Debs under the Espionage Act of 1917 for his words above, imprisoning him for ten years.

Cacophony is a spectacularly noisy word, no matter how quietly it's read.

In one of my favorite photos, my Mom has just climbed the last set of stairs leading to the open rooftop of a restaurant at the base of the Parthenon on a warm, cloudless night in Athens. It was the evening of her 63rd birthday, and waiting for her—a surprise that had been planned and kept tucked away for months—was her family. In the photo, she has her hand over her mouth—that wonderful human reaction to shock: the instinct to physically barricade word or sound (as if a hand really could), a recognition that the most appropriate immediate thing for the moment is noiselessness. Silence, even if only for the shortest second, before it gives way to all the volcanic emotion you must know was on its way.

Silencio (The Silencing Charm) is one that renders the victim temporarily mute. It is supposedly quite difficult to perform and you see it most when practiced by fifth years at Hogwarts in Professor Flitwick’s Charms class. (I started that book on a train back from New Jersey, read it early one morning on a bus to a race out in the Hamptons, and finished it in bed, the day before my birthday last year.) I remember this charm from the Battle of the Department of Mysteries (when Hermione used it against a Death Eater) and because she used it, his spell against her was significantly less harmful.

Poetic Terms:

caesura (n): a rhetorical break in the flow of sound in the middle of a line of verse; a pause, often set off by punctuation, marking a rhythmic point of division in a melody; from Latin caedere meaning "to cut." (see also: dramatic pause.)

enjambment (n): the running over of a sentence from one verse or couplet into another so that closely related words fall in different lines; the meaning carries over from one poetic line to the next, without terminal punctuation. (see also: run-on; It can make the reader feel uncomfortable or the poem feel like "flow-of-thought" with a sensation of urgency or disorder.)

I ran a marathon on my birthday, and around mile 20, a song I know well came on. It’s one I’ve been singing along to for years now, one I’ve seen performed dozens of times, and one I had never truly listened to (such is my relationship with lyrics). But somewhere, heading back out on my last lap along the water, my body really starting to yell a bit for some chocolate milk, one line stuck. It's the well-put truth that we have the time we have, from my great old friend, Nano:

Tried to steal another day, but that's just not allowed.

Arnold Hano, from his 1958 book, Baseball Stars:

There is no sound in baseball akin to the sound of Mantle hitting a home run. The crunchy sound of an axe biting into a tree, yet magnified a hundred times in the vast, cavernous, echo making hollows of a ball field.

David Halberstam, from his 1994 book, October, 1964:

Even the sound of his home runs, Dickey said, were different, mirroring something Ted Williams would say years later: the crack of the bat against the ball when Mantle connected was like an explosion. Henrich simply shook his head—it was one thing to hear about a coming star from an excited journalist, but quite another to hear it from someone like Bill Dickey.

I have spent so many rewarding hours reading books by Robert Caro and digging into articles about him and watching lectures he's given and listening to interviews with him. Last weekend, though, I actually got to see him speak at a beautiful old theater during the New Yorker Festival. He represents everything I adore about nonfiction, and there were more than a few times I was able to lean across after he was asked a question and whisper things to my brother like I bet he’ll tell the story about how LBJ lined up the last votes to get the Civil Rights Bill out of committee to which my brother would reply with something like yes yes and probably the one about the minor awards he won as a young journalist, too.

Coverage of the NAACP-organized Silent Parade of 1917, where thousands of African Americans marched down Fifth Avenue. Reported the New York Times: "Without a shout or a cheer they made their cause known through many banners which they carried, calling attention to 'Jim Crowism,' segregation, disenfranchisement, and the riots of Waco, Memphis, and East St. Louis." I wonder if this will feel as relevant in another hundred years as it does now.

I think Pablo Casals used to talk about—the great cellist from Spain, from Catalan—talked about infinite variety. And I think that’s what I seek in the mind’s eye. If you look at the, to quote Carl Sagan, “the billions and billions of stars out there,” and what stirs the imagination of a young child—you look at the sky and you start wondering, where are we? How do we fit into this vast universe? And to Casals saying that within the notes that he plays, he’s looking for infinite variety, to Isaac Stern saying the music happens between the notes.

OK, well, what, then, do you mean when you say music happens between the notes? Well, how do you get from A to B? Is it a smooth transfer—it’s automatic, it feels easy, you glide into the next note? Or do you have to reach to get to the—you have to physically or mentally or effortfully reach to go from one note to another? Could the next note be part of the first note? Or could the next note be a different universe? Have you just crossed into some amazing boundary, and suddenly the second note is a revelation?

— Yo-Yo Ma on music happening in the spaces between notes, from an interview, March 3, 2016

The call of the wild geese as harsh and exciting; the clear, strong pipes of the dipper’s voice; the melodious arguments of the goldfinches, and later, their discussion; the solemn and perfect music of the thrushes and his brothers; the crows, as they screech and scream at the owl; the rough and easy cry of the kingfisher; the kookaburras, how they ask her things; the silence after the loon cries as she waits under the thick pines; the meadowlark’s whistle, its breath-praise, its thrill-song, its anthem, its thanks, its allelulia: sweet, clear, and reliably slurring; the catbird, who is listening when he's not singing.

These are some of the euphonies of Mary Oliver’s birds.

Not often do I get off the subway at a train’s final stop. Perhaps the F to Coney Island or the G to Court Square in Queens. There’s nothing particularly exciting about it—the train will now pause and head back the other way—but there is there is something unavoidably human about the train’s behavior when it comes to rest. Right when it stops, when its trip from Brooklyn to Queens, from Manhattan to the Bronx comes to an end, it gives off a noticeably loud hiss—noticeably loud, so you almost have to look down to see if steam might appear from under the train. An audible moment of great exhale that always accompanies the end of a trip.

Compartment C Car, 1938, by Edward Hopper

Edward Hopper—the American realist painter, whose landscapes and people are strikingly alone and quiet and brooding—also had an interest in trains. As Alain de Botton describes:

He was drawn to the atmosphere inside half-empty carriages making their way across a landscape: the silence that reigns inside while the wheels beat in rhythm against the rails outside, the dreaminess fostered by the noise and the view from the windows—a dreaminess in which we seem to stand outside our normal selves and to have access to thoughts and memories that may not arise in more settled circumstances.

How many trips I’ve taken where this has shown itself to be entirely true. By train or car or bus. The journey as quiet as my mind is loud. And, like the F or G train, I also exhale when I get there.

From Absolutely On Music, the deeply personal, intimate conversations about music and writing between Haruki Murakami and Seiji Ozawa, the former conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

Seiji Ozawa: Now we’re completely in Glenn Gould’s world. He’s totally in charge now. In Japan, we talk about ma in Asian music—the importance of those pauses or empty spaces—but it’s there in Western music, too. You get a musician like Glenn Gould, and he’s doing exactly the same thing. Not everybody can do it—certainly no ordinary musician. But somebody like him does it all the time.

Haruki Murakami: Ordinary musicians don’t do it?

Seiji Ozawa: No, never. Or if they do, the spaces don’t fit in as naturally as this. It doesn’t grab you—you don’t get drawn in as you do here. That’s what putting in these empty spaces, or ma, is all about, isn’t it? You grab your audience and pull them in. East or West, it’s all the same when a virtuoso does it.

The beautiful gaps in the sentences of the old Trinidadian lady on Hospice that I visit. The mmmmmmhmmmmmms she uses as conjunctions that connect her clauses with sound, not pause. As in, These rice and beans mmmmmhmmmmm ain't they delicious? She can't see well anymore and she has a framed photo of Barack Obama over a couch patterned loudly with red and yellow flowers but her rhythms are happy and her smile is bright. Sometimes I don't even have to take the elevator to her floor because I'll walk in and hear a mmmmmhmmmmm from the little communal room on the ground-level and I know exactly where she is.

The same book, a later interview:

Seiji Ozawa: The same way different singers will sing the same phrase differently depending on whether or not they have the lung capacity. Do they have to take a breath or not? Some violinists can play the phrase with a single stroke of the bow and some cannot.

Haruki Murakami: Now that you mention it, Mann said a lot about the breath. When people sing, they have to take a breath at some point. But “unfortunately,” he said, string instruments don’t have to breathe, so you have to keep the breath in mind as you play. That “unfortunately” was interesting. He also talked a lot about silence. Silence is not just the absence of sound: there is a sound called silence.

Seiji Ozawa: Ah, that’s the same as the Japanese idea of ma. The same concept comes up in gagaku, and in playing the biwa and the shakuhachi. It’s very much like that. This kind of ma is written into the score in some Western music, but there is also some in which it’s not written. Mann has a very good understanding of these things.

Chet Baker is often my nighttime soundtrack, and though one is not louder than the other, it certainly feels more peaceful when he just plays his trumpet through the little speaker in my room, leaving his songs with lyrics in them for other nights. Just the instrument when I'm writing, please, and perhaps mix in a few lyrics when I’m making food. Salsas and pasta sauces and piña coladas my greatest specialties.

Maurice Sendak, from Open House for Butterflies (1960).

I asked my parents what triggered in them when I said the word silence:

Dad: For me, it is 2am in Casemasce and lying awake and the only sound I hear is an owl.

Mom: I thought of sitting quietly in Nature in meditation being aware of the sounds of Nature around me. Then I thought of moments under the night sky in Casemasce and Kalymnos.

Casemasce is the hilly and green place they lived in Umbria where you could see the Tiber River down below and the sky would open up at night—the garden was gorgeous and the herbs so very fresh. Kalymnos is the island they lived on in Greece—the water and sky fighting (helping?) each other to be the most blue. Dad talked about an owl, Mom capitalized the N in Nature, and both answers mentioned soft, natural noises backdropped with quiet. If you know my parents, neither of their answers would have surprised you, but they would have confirmed everything that makes you smile about them when you picture them answering that question from their road-trip through Southwest England, a fireplace certainly nearby, wine even closer, their togetherness a beautiful thing.

Snap, Crackle, and Pop—the trio of cartoon elves—have been the mascots of Rice Krispies since 1933. They’ve aged much the way Benjamin Button did, beginning old and rebranded with youth, and they drew their names from the sounds made by the cereal when milk interacted with them. Or, as an early radio ad put it: Listen to the fairy song of health, the merry chorus sung by Kellogg's Rice Krispies as they merrily snap, crackle and pop in a bowl of milk. If you've never heard food talking, now is your chance.

This is all a longer way of describing onomatopoeia, that lovely equals sign between word and sound.

Here's a study I found after my sommelier course last month:

British researchers asked 140 people to rate two identical wines. They tasted one wine after hearing the sound of a cork popping and one wine after hearing a screw-cap being opened. They were then asked to actually open both bottles and rate the wines again. Overall, participants rated the same wine as 15 percent better when served under a cork than a screw-cap.

Again, these were the same wines, and the only difference was the sound played when the wine was tasted. Or, as the study’s lead researcher said: “The sound and sight of a cork being popped sets our expectations before the wine has even touched our lips, and these expectations then anchor our subsequent tasting experience.”

Tacet is the instruction in a score that tells one instrument to be silent in the midst of the sounding of other instruments of the orchestra. And so, what if there was a piece where every instrument took this instruction simultaneously? Where no instrument was actually played? There is, and here is the direction to prove it:

4'33" by John Cage: four minutes and thirty-three seconds of silence.

A Zen story:

Once, a long time ago, there was a wise Zen master. People from far and near would seek his counsel and ask for his wisdom. Many would come and ask him to teach them, enlighten them in the way of Zen. He seldom turned any away. One day an important man, a man used to command and obedience came to visit the master. “I have come today to ask you to teach me about Zen. Open my mind to enlightenment.”

The Zen master smiled and said that they should discuss the matter over a cup of tea. When the tea was served the master poured his visitor a cup. He poured and he poured and the tea rose to the rim and began to spill over the table and finally onto the robes of the wealthy man. Finally the visitor shouted, “Enough. You are spilling the tea all over. Can’t you see the cup is full?”

The master stopped pouring and smiled at his guest. “You are like this tea cup, so full that nothing more can be added. Come back to me when the cup is empty. Come back to me with an empty mind."

Or, as Khenpo Pema Wangdak writes (in Spiral, the publication from the Rubin Museum of Art, which accompanies their incredible exhibition, The World is Sound):

Silence is fascinating because it is equivalent to emptiness, one of the main messages of Buddhism. The simplest way to explain silence is to call it the absence of sound, while emptiness is the absence of everything. In Buddhism we say, “That which is empty, everything is possible. That which is not empty, nothing is possible.” To apply this to the idea of sound, I’d say, “That which is silent, everything is possible.”

Before Clint Eastwood showed his conservative senility in his sad speech to an empty chair at whatever tragic adjective you'd like to use to describe a Republican National Convention, he had a place of much greater esteem in my mind. Edward and I used to watch everything he ever did, sometimes betting on how many minutes after the movie began it would actually take him to say his first word. His paucity of word was both impressive and deliberate: I heard somewhere that the first thing he’d do with a new script is red-line it—nope, not saying this, he’d say. Or this or this or this.

Pleading the Fifth is a term for invoking the right that allows witnesses to decline to answer questions where the answers might incriminate them, and generally without having to suffer a penalty for asserting the right. This right to silence also exists upon arrest (as in, Miranda rights).

There are, therefore (in theory, at least), federal criminal procedure protections granted to us designed to shield ourselves from the potential harm of our very own words.

One Square Inch of Silence proclaims itself to be: "the quietest place in the United States," that was "designated on Earth Day 2005 to protect and manage the natural soundscape in Olympic Park’s backcountry wilderness." Why?

The logic is simple; if a loud noise, such as the passing of an aircraft, can impact many square miles, then a natural place, if maintained in a 100% noise-free condition, will also impact many square miles around it. It is predicted that protecting a single square inch of land from noise pollution will benefit large areas of the park.

Here is my favorite part (I bolded the piece I love the most):

The publication of the location of One Square Inch increases the likelihood of visitation by hikers. Your visit is encouraged. Please be quiet. It is the belief of this organization that the need for quiet and the power of quiet will foster the care needed to preserve this site. At the site is the Jar of Quiet Thoughts, a depository of notes left by visitors. You are welcome to read and add to the Jar. Please respect that these are quiet thoughts from a quiet place—no quotes from the Jar are allowed.

The margins of my books, as is the case with some of the insides of their covers, are loud with notation.

Maurice Sendak, from Open House for Butterflies (1960).

Says the intriguingly moral Edmund Bertram in Mansfield Park to Fanny:

I am worn out with civility. I have been talking incessantly all night, and with nothing to say. But with you, Fanny, there may be peace. You will not want to be talked to. Let us have the luxury of silence.

Silence here is a relief, a "luxury"—a very sardonic Jane Austen take on it. It can be more grim elsewhere in fiction. Take Heathcliff’s unexplained three-year break from Wuthering Heights. He leaves in torment, and comes back smarter, wealthier, and vengeful—we can guess about what happened during those years (as we can about Wentworth’s long absence in Persuasion, though we do know more about what he was up to), but they are never discussed in the book. His absence, his silence about these years becomes a presence in the book of great weight. It is truly shaping, making Heathcliff the difficult, Byronic, romantic hero he becomes.

I have great qualms over the way we report and handle tragedy. The threefold response can often progress:

- It's too soon to discuss (i.e., for now, keep quiet)

- It's ok to remember (i.e., let's share a moment of silence)

- It happened so long ago (i.e., what possible value can be gleaned by continuing to talk about it?)

Of course, this is drastically formulaic and oversimplified, but it would be hard to find a tragedy—from 9/11 to mass shootings—that still does not contain at least one of these elements. Which is why I enjoyed this recent story, my favorite dismantling of what I consider to be an exceptionally fraudulent way of meeting difficulty (second only to the plague of "thoughts and prayers" that seem more self-indulgent than anything else):

A night after he and the other late-night hosts worked through their grief and anger about the massacre in Las Vegas and Republicans’ “thoughts, prayers, and literally nothing else” response to the shooting of 600 people by one man with a whole lot of military-grade weaponry, Trevor Noah invited a congressman...to offer some alternatives.

Representative Jim Himes (D-CT) came on The Daily Show to talk about gun control, as he did after another nation-rocking mass shooting back in 2016. After joking that they only meet after horrible gun-related mass murders, Noah added that “it feels like there is always a mass shooting to see you after,” before asking noted gun control advocate Himes what Congress should and actually will do after this latest horrific mass shooting. (The 273rd in 275 days this year, for those who are counting.)

Himes dismantled the hypocrisy of his congressional colleagues who hold mandatory moments of silence for victims of gun violence while using the time directly after those moments to vote against any gun restrictions of any kind. Explaining his decision to not participate in this most recent meaningless gesture, Himes said, “If you’re in the one room where you can start fixing this problem that no other country has” and your only response is to not talk for a minute, then “that’s negligent, that’s not honoring anybody.”

On December 3, 1926, Agatha Christie's car was found abandoned at the Silent Pool near Albury, in Southeast England—she was nowhere to be found. She turned up eleven days later, and to this day, nobody knows what happened while she was gone.

Edwidge Danticat, Haitian author, in an interview at the New York Public Library, September, 2016. Here, she's talking about her fascination, her obsession, with silence:

I feel like that’s always changing, you know, these obsessions, and maybe they’re sort of different formulations of the same obsession, which is—I think [silence] has a lot to do with separation because, you know, for a lot of us, when you were kids growing up in a dictatorship...there’s always this code of silence of things that couldn’t slip, so I’m intrigued by silence, silence that’s forced by outside and circumstances...

Junot Díaz, Dominican author, in an interview at the New Yorker (after he has read a chapter of one of Danticat's books), February, 2017. Here, after a long back-and-forth about the many silences he just read, he takes a moment to speak more broadly:

There is no better way to increase the silences in families and the silences between people than immigration. I think perhaps only war comes close, or exceeds it.

Two writers, woman and man, born months apart on the same island (though different countries), both immigrants writing about immigration, both exploring silence—in all its corrosive, shaping, imposed power.

By all outward appearances our life is a spark of light between one eternal darkness and another.

—The Wisdom of Insecurity, Alan Watts

The rest is silence.

—Hamlet, Shakespeare, Act V, Scene ii (Hamlet's last words)