The Little Gaps That Separate Everything

If you weave your way through a set of narrow roads and head mostly northwest from the main port in Kalymnos, you’ll get to Kastelli. It’s a hilly and rugged terrain, but the goats and bees seem to love it and even though the mopeds struggle as they climb, everyone is happily running a step slower anyway. The Aegean Sea helps motivate this calm, I think, offering a lot to pause about: a sailboat or two out toward the horizon. The profound blue of the water, the sun and sand conspiring to turn it turquoise as it gets closer to shore. A number of islands – near and far – that hold single churches, a restaurant or two, a path up to a cave, or perhaps, nothing at all. Even now, there’s a foam-trail behind a slow-moving fishing boat.

More near to me is a hammock hanging from a post by the pool which, when unoccupied, suggests the strength and direction of the wind. Then there’s a charcoal oven out back with a bricked top that looks perfect for making a pizza or two, and a couple of racks nearby if you’d like to grill some fish instead. I’m in the shade now and will run to a little beach later. My family is headed that way, too, all from different directions, and we’ll swim and have a few beers and let the sun drop to its probably-nearly-time-for-dinner angle. So then we’ll have dinner.

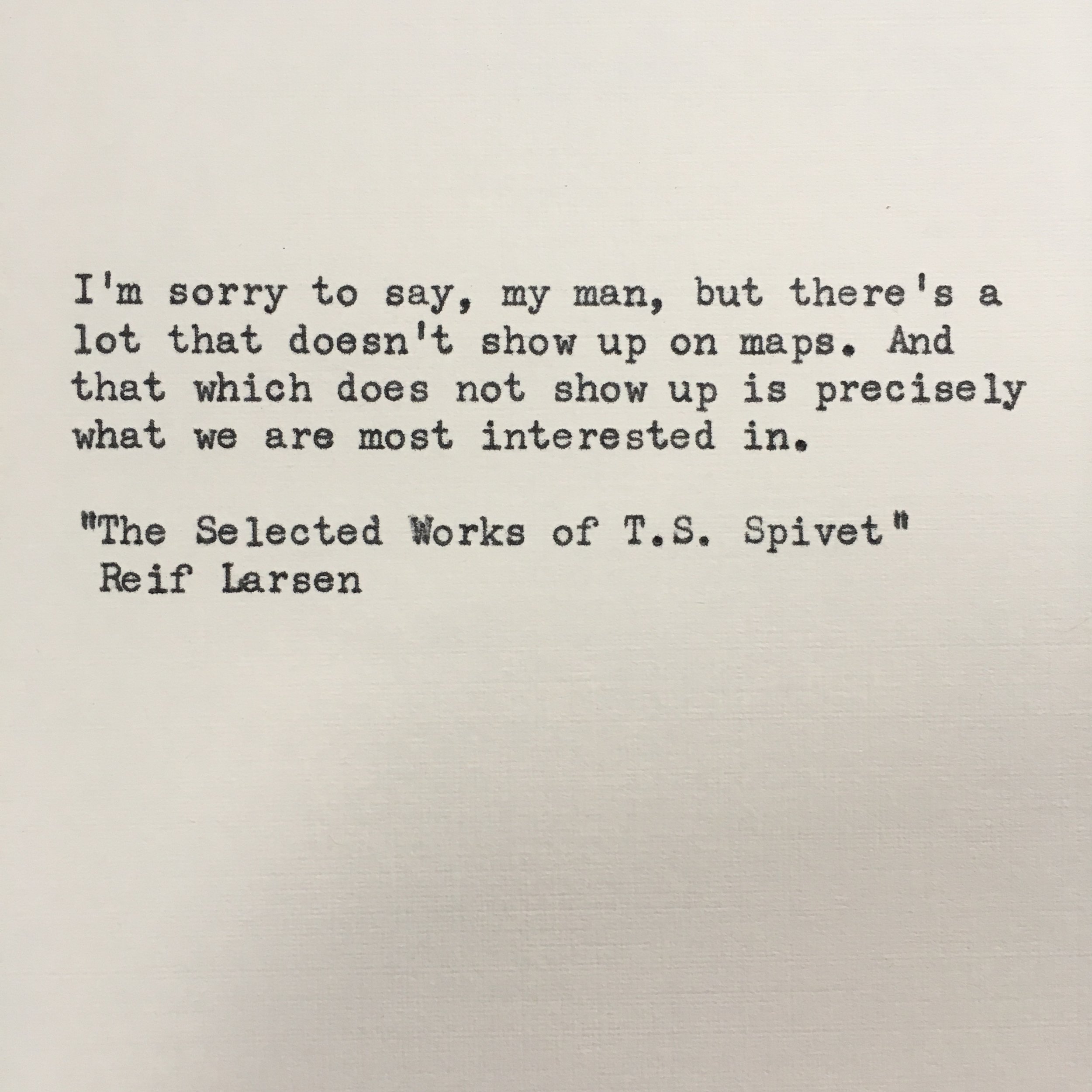

I’m lucky. I am. To have moments like these string together, to have the family that goes out of its way – genuinely – to create them, and to have the privilege of being able to write the first two paragraphs as I have. And somewhere amidst them all, I’ve also found myself taking time to do what Emma Bovary’s father did in the quote you see: drop his pen and wonder.

I love a meandering mind, and I also love the idea that the spaces separating things – as in rest in music, pauses in speech, or in this case, gaps between lines – somehow affect meaning and impact. In some cases, the emptiness can give birth to something exceptional. Sherlock Holmes, for example, was born out of the idle moments in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s ophthalmology practice. Jennifer Egan’s wonderful book, A Visit From the Goon Squad, has an entire chapter devoted to pauses, spaces, and gaps.

This is one of those rather anonymous lines I find to be quite beautiful. It comes in the middle of a scene where one of the book’s more sympathetic characters, Emma’s father, is writing to his daughter. What a picture it creates, almost of a breath or an exhale, something timelessly human about searching or thinking or exploring. I do that often here.

And how about this: collect those gaps, line up those pauses into a row of silence, and that fraction of space can be even more delightful. And profoundly more difficult, too.

This is an excerpt from 4'33", John Cage’s three-movement composition that premiered in 1952 at a small concert hall in Woodstock, New York. Unlike anything he had ever played before, David Tudor walked across the stage, sat down at the piano, opened the score (which said, in part, tacet – or “silence”), and followed it perfectly: he touched not a single key. He then left the stage.

It’s an easy thing to condemn, but in Where the Heart Beats – one of the most incredible books I have ever read – Kay Larson explores the life of Cage, as he grew from an avant-garde musician who played with sound and noise and silence, into a man deeply affected by Zen Buddhism. There is nothing gimmicky about 4'33", in fact, as you learn about his life and his tendencies, you realize it is the ultimate expression of Cage’s music.

Silence (or, creating a space that allows many other sounds to drift in and out), the ability to sit moment-to-moment without judgment, not fighting for certainty, and not dismissing something because it defies our perceived idea of what it is supposed to be – these four things are immensely difficult.

But now, as I’m starting to eye my running shoes a little more and know that my family is probably gathered waist-deep in the water chatting away and feel like I want my skin to feel that salt-watery crust that sometimes happens after a day of sun and swimming, it’s not the silence I want anymore, it’s its happy, contrasting friend – one that urges release, the letting go into those simple, irreplaceable moments:

I did think, let’s go about this slowly.

This is important. This should take

some really deep thought. We should take

small thoughtful steps.

But, bless us, we didn’t.

This is from Felicity, which feels like the closest Mary Oliver has come to Rumi. Indeed, the epigraphs throughout belong to him, my favorite of which begins everything: You broke the cage and flew. It really is like reading a collection of little meditations.

As in, her poem about moments (actually called just that: Moments):

There is nothing more pathetic than caution

when headlong might save a life,

even, possibly, your own.

And how nicely does it pair with simplicity! From Storage:

Things!

Burn them, burn them! Make a beautiful

fire! More room in your heart for love,

for the trees! For the birds who own

nothing – the reason they can fly.

Whenever I read that, I think of my first room in New York that snugly held my bed and two stacks of books on the floor. On a furnace that acted as a shelf, a Buddha sat next to a candle with his hand on the ground and it’s the first thing I would see if I woke up on my right side. There was a Mets calendar pinned to one of the walls and a few race numbers on another. Much more than that – though I have always loved my portable little speaker – got to be too noisy for me.

Simple and beautiful moments separated by simple and beautiful gaps. The happy chatter of your family in the sea. The small brown bag of books and running shoes and a shirt or two and some shorts or two. Salt water and skin that’s catching the sun and getting a little browner. The delicious dolmas at dinner that match perfectly with slightly chilled Greek red wine that pours from a carafe.

Yes yes yes. I will drop my pen, too, and think of these things for a while. They are what matter.